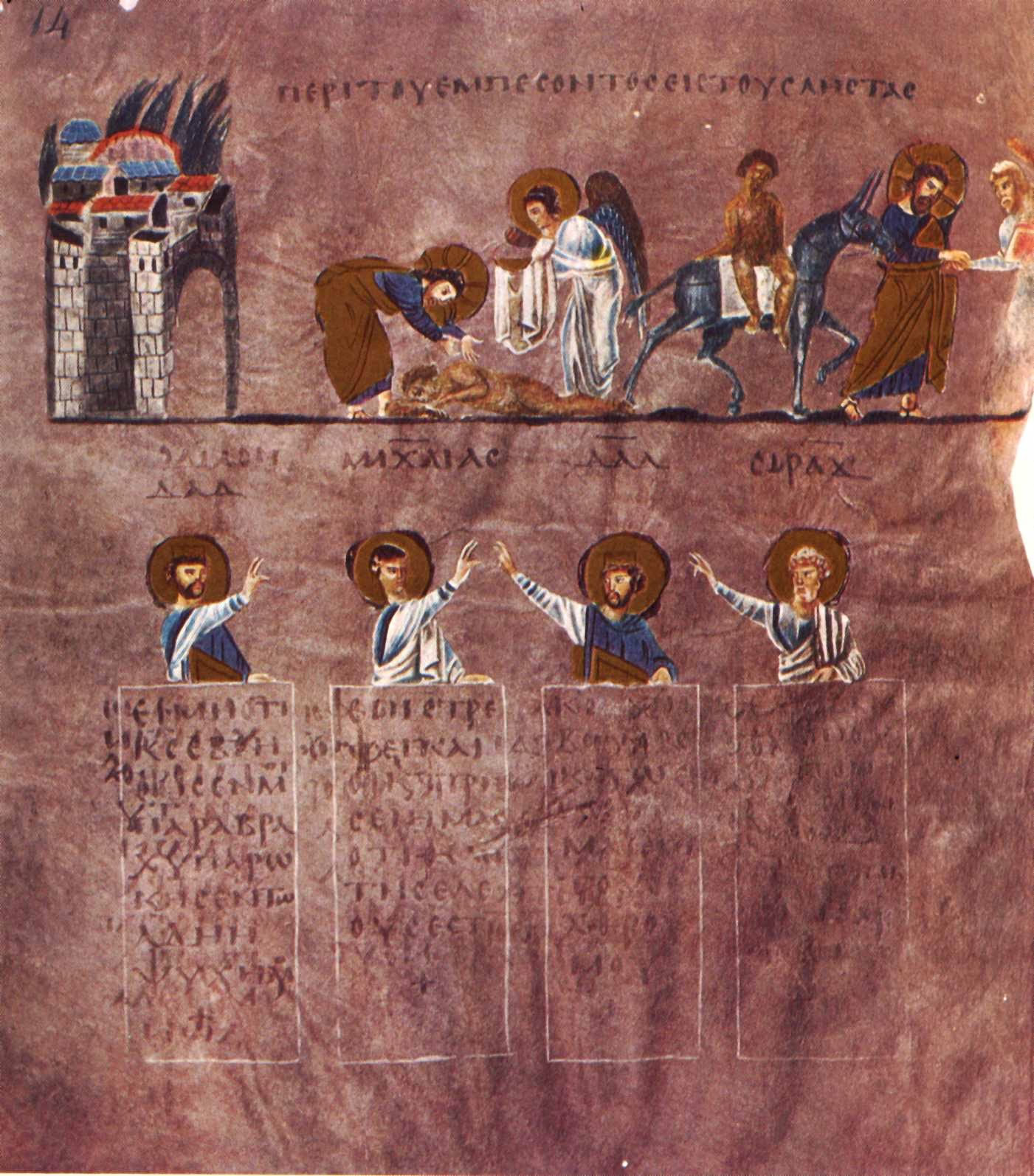

The Rossano Gospels: The Parable of the Good Samaritan

Older Bibles were illuminated – that means illustrated or decorated with drawings – and in the 6th-century, a manuscript called the Rossano Gospels were put together. It is also known as the Codex Purpureus Rossanensis due to its reddish (purpureus in Latin) pages, and it is one of the oldest surviving illuminated manuscripts of the New Testament. It can be found in the Cathedral of Rossano in Southern Italy.

One of the drawings depicts two scenes from the parable of the Good Samaritan. One shows the Samaritan caring for the victim and another where the Samaritan entrusts the victim to an inn-keeper. In this last scene, he is shown paying the inn-keeper. What makes this particularly interesting is that the Good Samaritan has a halo with a cross. If it looks like Christ, it is because we are meant to see the Good Samaritan as an allegory for Christ.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan can be found in chapter 10 of the Gospel according to Luke. In a nutshell, a man was robbed of his clothes and possessions and was left half-dead. A priest and a Levite ignored the man, but a Samaritan took compassion and took care of him. He also carried him and took him to an inn where he gave him to an innkeeper with instructions to, “take care of him” until he returns, with the promise to pay for whatever cost was incurred.

When viewed in the context of the Gospel, Christ is trying to teach what all the commandments have been trying to teach: if we love God, we must love others. Simply put, if we have faith, that faith must be translated into action towards others. In the case of the parable, Samaritans and Jews did not customarily go together. In fact, Samaritans were shunned by the Jews. But in the parable a priest, and a Levite, which is a priestly class, both failed to translate their faith into good works. Instead, it was the outcast who did.

While this lesson is plain to see, the Church Fathers (Irenaeus, Clement, Origen, Ambrose, and Augustine) point out that there is another dimension in this parable wherein we can see the Church. If we consider that mankind was robbed of his original holiness during the Fall, we can see mankind in the person of the parable’s victim. We can see more of the parallelism when the parable describes him as “half-dead” because when we lost sanctifying grace, mankind became half-dead: physically alive, but spiritually dead. To continue the allegory, the fallen angels are the thieves, the priest and Levite represent the priesthood of the Old Testament that can no longer help in salvation.

Christ, then, would be the person who takes compassion and rescues the victim. The word Samaritan means “guardian” and describes Christ. When the Samaritan binds the wounds of the victim, it represents Christ binding or “restraining” sin. Scripture has always presented Christ as an outcast. He was born in Bethlehem while his parents were there on a journey, and where every inn-keeper rejected them. Also, he was not recognized by the scribes and Pharisees as the Messiah. It is apt that the rescuer in the parable is an outcast Samaritan.

The parable describes the Samaritan as lifting the victim during the rescue. When Christ saved mankind, he did not wave a magic wand and made all things right again. The second person of the Trinity came down, became one of us, and through his death and resurrection opened heaven and, through his help, lifts us up.

Finally, the Samaritan places the victim in the care of an innkeeper. We can see in this that Christ entrusts us to the care of the Church until his return at the end of time, just as the Samaritan promised he would return. Whatever debt was incurred to patch up mankind’s broken relationship with God through disobedience was paid by Christ through his Passion and Death.

If this other dimension of the parable is true (and it is quite difficult to argue against it because of all the parallelism) then it means Christ has always meant for a Church to exist in some physical way otherwise it cannot care for its members. In fact Catholics have always seen the Church as a hospital for sinners – very much the way the inn keeper’s lodge was a refuge for the victim.

Next time we encounter this parable, let us consider this other dimension and see that the Church was part of God’s loving plan, to be our mother, until his return. Since we are part of this living organism, we must contribute to its health and growth.