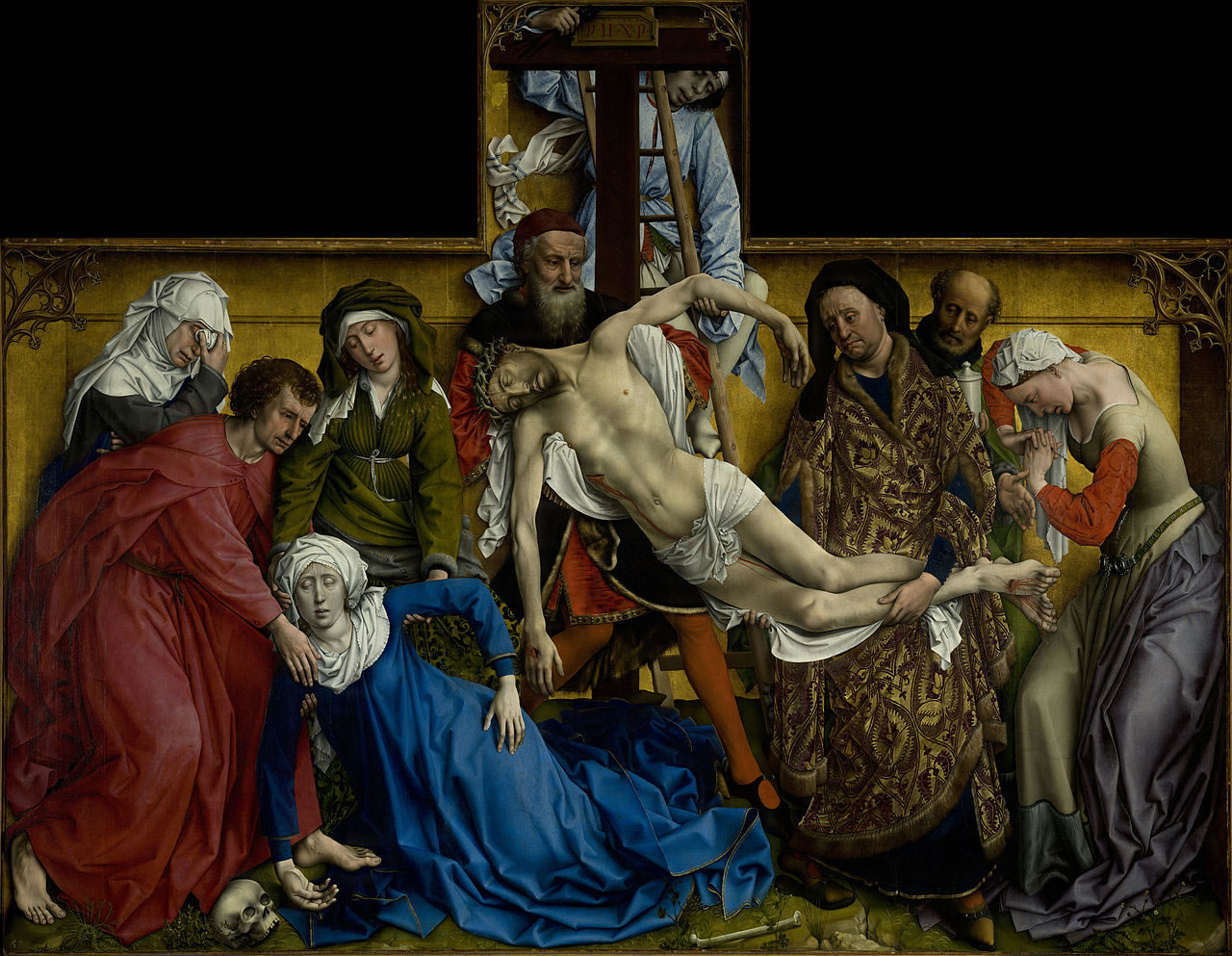

The Descent from the Cross

The Descent of the Cross by Roger Van Der Weyden is considered a masterpiece of its time. The life-sized painting depicts the deposition of Christ (removal from the cross) by Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea.

Art scholars like to attribute its beauty to the remarkable way the painting captures the emotions of the people depicted in it. Mary of Clopas, on the upper, left is weeping (they all are) with a piece of cloth to dry her eyes. John the apostle on the extreme left bends his body to support Mary the mother of Jesus, while Mary Magdalene on the extreme right also bends her body in grief at seeing her dead Lord. Both John and Mary Magdalene seem to form a pair of parentheses that group everyone.

There are three striking things we can learn from this painting. The first is that Mary, the mother of Jesus, has fainted and her body takes the same shape as her son. It is a visual artist’s way to illustrate how Mary was so configured to Christ that she united herself to his passion – so conformed that even their bodies are choreographed as if in a dance. Arnold of Chartres said, “The wills of Christ and of Mary were then united, so that both offered the same holocaust. In this way she produced with him the one effect, the salvation of the world.”

Lest our Christian brothers and sisters may think we are elevating Mary to savior status, we must remember Christ is our one and only savior. Mary only joins her sorrow (at seeing her son tortured and crucified so cruelly) to his. Aren’t we asked to do the same when we are suffering? That way we “cooperate” with Christ suffering. The only difference is that Mary does it perfectly as she completely abandons her will to God. This is why we call her Co-Redemptrix (co-redeemer) – a title that refers to her role in the redemptive work of Christ.

In her fainted state, Mary becomes a metaphor for the Resurrection of Christ. The similar position of both alludes to a parallel conclusion: Jesus will come out of his death that same way Mary will come out of her fainted state as if both were just sleeping.

The second thing we can learn from this painting is from the skull and bone in the bottom foreground. It does allude to the name of the place where Christ was crucified: Calvary or in Latin “Place of the skull”. While that is apparent, there is a deeper meaning. Early Christians saw Calvary as a “new Eden.” Whereas Adam brought “death” to our human nature in Eden, Christ’s death brought life in the new Eden. So the bones we see in the painting belong to Adam, while Jesus is the New Adam (as St. Paul refers to him) and also the new Tree of Life. Mary is the new Eve. Eden was a garden, while Calvary also had a garden. The fountain that watered the world emanated from Eden (from Genesis), while the everlasting fountain of life, the blood from the side of Christ, emanates from the new Eden. What we can learn is that the story of salvation is a poetic one, and poems don’t just happen by chance – someone has to orchestrate the rhyme and rhythm.

The last thing we can learn from this painting is that Christ is our King and his throne is the cross. Another name for this painting is “the Deposition of Christ.” The word “depose” is used when a leader is taken away from his position. While it can be used to describe Presidents removed from office, it is used most correctly when describing a king being taken away from his throne. Because we no longer live in times when monarchs are “deposed”, the real meaning of the word is lost on us. Knowing its meaning now, it is clear that when we use the word “deposition” in Christ’s Passion, we are stating that the cross is the throne from where he reigns. (It doesn’t mean Christ was removed from his position as King.) What this means is that we must be ready to face our own suffering for if our king reigns from a place of suffering, how can we be expected to do any less. We should not forget that we are saved, not from suffering, but through it.

10/26/18